One of the services we offer at The Productive Pessimist is public speaking, remotely or in person, both as sole speaker and as panel members.

One of the topics we offer public speaking on is that of living car free. This topic is covered in depth by myself - Ash - and centred in the 20yrs I have been obliged to spend living car free, with half that time spent living in small villages in rural Norfolk, travelling up to 40miles each way for work, in full time employment.

How It Started

When I was 19, I took my third - and, as it turned out, final - driving test. I failed, and in such a way that I was referred for a fitness to drive sight test. I failed this, as well, with the commentary that my peripheral vision was very limited, and I therefore wasn't considered safe to drive.

When I'd failed the driving test, I had a severe panic attack, and expressed to my instructor that "My parents are going to kill me" - I paid for my driving lessons, but my Dad paid for my driving tests. My mother made it very clear that this was a considerable hardship - even 20yrs ago, driving tests were expensive.

When I was told I was medically unfit to drive, I experienced, initially, a period of intense depression; my understanding was that not being able to drive would end any chance of having a productive life, and prevent me from ever being "a real man". (The link between driving and independence, and independence and masculinity, is one I explore more fully in talks I'm commissioned to give about living car free.)

One of the topics we offer public speaking on is that of living car free. This topic is covered in depth by myself - Ash - and centred in the 20yrs I have been obliged to spend living car free, with half that time spent living in small villages in rural Norfolk, travelling up to 40miles each way for work, in full time employment.

How It Started

When I was 19, I took my third - and, as it turned out, final - driving test. I failed, and in such a way that I was referred for a fitness to drive sight test. I failed this, as well, with the commentary that my peripheral vision was very limited, and I therefore wasn't considered safe to drive.

When I'd failed the driving test, I had a severe panic attack, and expressed to my instructor that "My parents are going to kill me" - I paid for my driving lessons, but my Dad paid for my driving tests. My mother made it very clear that this was a considerable hardship - even 20yrs ago, driving tests were expensive.

When I was told I was medically unfit to drive, I experienced, initially, a period of intense depression; my understanding was that not being able to drive would end any chance of having a productive life, and prevent me from ever being "a real man". (The link between driving and independence, and independence and masculinity, is one I explore more fully in talks I'm commissioned to give about living car free.)

How It's Going

I had a varied experience in the first 10yrs of my time without the means to drive, something I discuss in my talks on the topic. In the last decade, however, the challenges not having a car, and not being legally able to hold a driving licence, presents actually seem to be increasing, rather than being eased by improved technology.

I spent the first 10yrs of the 20yrs I've been excluded from being able to enjoy the privileges that come with being legally permitted to drive living in somewhat isolated, rural villages in distant areas of Norfolk. At times, I had to travel 40miles each way to work, with none of my colleagues coming from even partly the same direction, and thus without the option of getting a lift from anyone. For part of that time, I lived two miles from the nearest shop.

For the last decade, I've lived in a town, with five 'corner shops' within five minutes' walk of my front door, two of them within 2mins' walk, and an entire town centre, with three separate supermarkets, two shoe shops, several clothes shops, and other diversions, just 10mins' walk away. There is a regular bus service, both to the two closest towns, and to the nearest city. The bus station is just 8mins' walk from my front door. There are also frequent trains which join the mainline services at Ipswich and Norwich, and the railway station is only about fifteen minutes' walk for me. In theory, there is considerably more employment very locally than I ever benefited from in the first 10yrs of my experience of coming to terms with the fact that driving was not something I would be getting to enjoy.

However, it is actually more challenging to get by without a car now than it was previously, in a more remote area, with less technology available to mitigate the impact of not being able to drive.

Why Are Things Worse Now?

Improvements in technology should mean it is easier to live without a car than it ever has been - but the opposite seems to be true, both from my own direct experience, and from the reactions of car drivers to suggestions that they might reduce their dependencies.

Technology has progressed very rapidly, and has the potential to truly transform the way people across the world live, and the quality of the lives they get to live.

The problem with that is that truly transformative change requires extensive, and genuinely open and open-minded, communication with everyone who will be impacted, positively, negatively, and in ways which cannot be predicted, by all possible manifestations of transformation, and that communication has never happened, and is still being refused, where technology is concerned.

My experience of leading transformative change projects has been that you need to communicate about the proposed change for fully half the time that has been committed to the project, before you even begin, in order for the change to become wanted, welcomed, and fully facilitated.

If your project is estimated to take 18mths to implement, you need to spend 9mths, before you even start the initial processes, communicating across all levels, and to both direct and indirect stakeholders, about the project, the change it's going to bring, the drivers for that change, and the real-world, immediately-observable impacts, both positive and negative, of the change, both as it develops through the project lifecycle, and as it embeds into a new "everyday."

Technology seems to be a series of small projects, but is actually just one large, multi-generation project. Everything we see as "another technology project" is simply a stage in the vast, complex project that is technology.

And there has been no real communication about "Project Technology", much less the extent of communication that is needed for a project of this size and scope.

Because of this, technology is still viewed with suspicion by many, and as distinctly undesirable for large swathes of those who control the demands placed on the lives and time of ordinary working people. This means that the ability of technology to remove the negative implications of not having access to a vehicle, or the lawful means to drive, is hampered by the limitations of the understandings of those who dictate the lives of the majority.

Many of the stakeholders who should have been consulted before "Project Technology" put forward its first tentative suggestions for change have extremely vested interests in people continuing to rely very heavily on motorised transport. Because they were not consulted, they feel an intense resentment to technology entirely. It isn't too late to consult them now, but the work of doing so is considerably harder than it would have been 40yrs ago, when "Project Technology" was first being rolled out in a mainstream, democratically accessible fashion.

This lack of communication is impacting the least privileged, as a lack of communication always does. It is holding back those who are legally and medically banned from driving, many of whom are disabled. It is holding back people of the most limited financial means. It is keeping the most socially isolated in isolation, with all the damaging impacts on mental health, emotional stability, and physical wellbeing that we observed very starkly with the Covid-19 lockdowns.

Whenever the least privileged are held back, society itself is prevented from progressing to its fullest potential.

Belief Barriers to Going Car Free:

. "I wouldn't be able to get to work!" - For three years, I travelled 40miles, by two buses and a twenty-five minute walk, to a job which paid less than £20,000 a year, and demanded five days a week, with 10hrs' work per day.

I worked without a lunchbreak to accommodate the fact that, even taking the earliest possible buses in each occasion, I was thirty minutes late, and needed to leave twenty-five minutes early in order to catch the last bus back into the city centre.

On several occasions, that bus refused to stop, and I had to walk 6miles back into the city centre, to catch a bus home; three of those six miles were alongside an unlit, 60mph stretch of busy road, where there was no pavement, and the verge was too steep to be safely accessible for walking.

I've lost 3 jobs because I am reliant on public transport, something which would not have happened if people having the ability to drive their own car were not assumed to be the case for everyone, and taken for granted.

I had a varied experience in the first 10yrs of my time without the means to drive, something I discuss in my talks on the topic. In the last decade, however, the challenges not having a car, and not being legally able to hold a driving licence, presents actually seem to be increasing, rather than being eased by improved technology.

I spent the first 10yrs of the 20yrs I've been excluded from being able to enjoy the privileges that come with being legally permitted to drive living in somewhat isolated, rural villages in distant areas of Norfolk. At times, I had to travel 40miles each way to work, with none of my colleagues coming from even partly the same direction, and thus without the option of getting a lift from anyone. For part of that time, I lived two miles from the nearest shop.

For the last decade, I've lived in a town, with five 'corner shops' within five minutes' walk of my front door, two of them within 2mins' walk, and an entire town centre, with three separate supermarkets, two shoe shops, several clothes shops, and other diversions, just 10mins' walk away. There is a regular bus service, both to the two closest towns, and to the nearest city. The bus station is just 8mins' walk from my front door. There are also frequent trains which join the mainline services at Ipswich and Norwich, and the railway station is only about fifteen minutes' walk for me. In theory, there is considerably more employment very locally than I ever benefited from in the first 10yrs of my experience of coming to terms with the fact that driving was not something I would be getting to enjoy.

However, it is actually more challenging to get by without a car now than it was previously, in a more remote area, with less technology available to mitigate the impact of not being able to drive.

Why Are Things Worse Now?

Improvements in technology should mean it is easier to live without a car than it ever has been - but the opposite seems to be true, both from my own direct experience, and from the reactions of car drivers to suggestions that they might reduce their dependencies.

Technology has progressed very rapidly, and has the potential to truly transform the way people across the world live, and the quality of the lives they get to live.

The problem with that is that truly transformative change requires extensive, and genuinely open and open-minded, communication with everyone who will be impacted, positively, negatively, and in ways which cannot be predicted, by all possible manifestations of transformation, and that communication has never happened, and is still being refused, where technology is concerned.

My experience of leading transformative change projects has been that you need to communicate about the proposed change for fully half the time that has been committed to the project, before you even begin, in order for the change to become wanted, welcomed, and fully facilitated.

If your project is estimated to take 18mths to implement, you need to spend 9mths, before you even start the initial processes, communicating across all levels, and to both direct and indirect stakeholders, about the project, the change it's going to bring, the drivers for that change, and the real-world, immediately-observable impacts, both positive and negative, of the change, both as it develops through the project lifecycle, and as it embeds into a new "everyday."

Technology seems to be a series of small projects, but is actually just one large, multi-generation project. Everything we see as "another technology project" is simply a stage in the vast, complex project that is technology.

And there has been no real communication about "Project Technology", much less the extent of communication that is needed for a project of this size and scope.

Because of this, technology is still viewed with suspicion by many, and as distinctly undesirable for large swathes of those who control the demands placed on the lives and time of ordinary working people. This means that the ability of technology to remove the negative implications of not having access to a vehicle, or the lawful means to drive, is hampered by the limitations of the understandings of those who dictate the lives of the majority.

Many of the stakeholders who should have been consulted before "Project Technology" put forward its first tentative suggestions for change have extremely vested interests in people continuing to rely very heavily on motorised transport. Because they were not consulted, they feel an intense resentment to technology entirely. It isn't too late to consult them now, but the work of doing so is considerably harder than it would have been 40yrs ago, when "Project Technology" was first being rolled out in a mainstream, democratically accessible fashion.

This lack of communication is impacting the least privileged, as a lack of communication always does. It is holding back those who are legally and medically banned from driving, many of whom are disabled. It is holding back people of the most limited financial means. It is keeping the most socially isolated in isolation, with all the damaging impacts on mental health, emotional stability, and physical wellbeing that we observed very starkly with the Covid-19 lockdowns.

Whenever the least privileged are held back, society itself is prevented from progressing to its fullest potential.

Belief Barriers to Going Car Free:

. "I wouldn't be able to get to work!" - For three years, I travelled 40miles, by two buses and a twenty-five minute walk, to a job which paid less than £20,000 a year, and demanded five days a week, with 10hrs' work per day.

I worked without a lunchbreak to accommodate the fact that, even taking the earliest possible buses in each occasion, I was thirty minutes late, and needed to leave twenty-five minutes early in order to catch the last bus back into the city centre.

On several occasions, that bus refused to stop, and I had to walk 6miles back into the city centre, to catch a bus home; three of those six miles were alongside an unlit, 60mph stretch of busy road, where there was no pavement, and the verge was too steep to be safely accessible for walking.

I've lost 3 jobs because I am reliant on public transport, something which would not have happened if people having the ability to drive their own car were not assumed to be the case for everyone, and taken for granted.

. "How would I cope with the kids?!" - Folding pushchairs, which make it easy to take children on a bus without preventing wheelchair users from accessing the designated space provided for them are available, as are papooses, which are suitable for carrying babies too young to be in a pushchair.

From the time I was 10yrs old, I was cycling to anything I couldn't walk to, that I wanted to attend, on my own. From the age of 7, my Dad would bike with me there and back. (I never asked what he did between the time an event started, and when it finished - suggestions on a postcard, please!) Some things, I was just told "No" about doing - it was too far to walk or cycle. For most of my childhood, my parents didn't have a car, because they couldn't afford one. Once they had a car, the point that "petrol is expensive" still governed how, and if, the car was used. Social enrichment was typically not considered something that it was 'necessary' to spend out on petrol for.

I learned to be comfortable with minimal diversions.

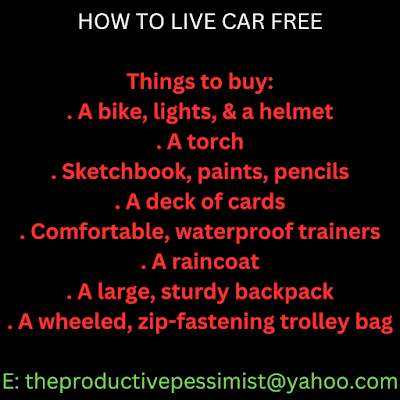

I never knew, and still don't, about 'boredom' - as long as I have a deck of cards, books, a notepad and pen, or even just space to do press ups, I don't feel the impact of either isolation or lack of occupation.

I know how to hold conversations, because conversation was something I had to go to significant effort to engage in.

All of these are important, necessary life skills, which were found sadly lacking during the Covid-19 lockdowns.

. "And how am I meant to do the big shop?! They don't do home delivery where I live!" - when I lived in rural Norfolk villages, "home delivery" from supermarkets wasn't a thing for anyone. Even takeaways didn't deliver to two of the three villages I lived in during that time. Supermarkets required either a walk - at one point, of five miles - or a bus journey. Grocery shopping was something that had to be planned, and even now, when I have many shops within easy walking distance, and home delivery is available, I am able to cope without instant gratification of desires for snacks, or takeaway food. I am able to cope with "the food we have in the house", however uninspiring that can sometimes seem. Do I enjoy having the ability to satisfy cravings? Yes - but I am able to indulge it responsibly, and to recognise it as an exceptional privilege, not simply "the way things are."

. "It's too dangerous to walk or cycle!" - I would agree. I've been knocked off my bike three times by cars, twice by drivers who didn't even stop to see if I was okay. I've been threatened with arrest by police for walking alongside a road, and, especially as my sight has declined significantly, nearly being run over is a near-daily experience - and a threat that increasingly intrudes on the pavement, where I should be enabled to feel safe, thanks to cyclists who think their lack of competence and confidence riding in traffic needs to be made the problem of pedestrians.

But if everyone who thought they "had to" use a car because "it's not safe on the roads" took their car off the roads, the roads would rapidly become safer.

. "There's no buses round here/public transport's too expensive!" - at one point, I was paying over £2,000 a year just to be late to work, and to have to give up my lunchbreak, and leave work early.

I was assaulted twice on buses during my return journeys, and verbally abused on several occasions. Every morning, I had to deal with feeling extremely unwell, because other people travelling on the same bus I had to take smoked cannabis - I'm allergic to THC. It causes migraines, and makes me feel exceptionally nauseous. On two occasions, I was accused of using cannabis by my boss, because the smell from joints being smoked by those waiting for the bus with me transferred to my clothing - cannabis is illegal in the UK, and being under the influence of any drug was against my employer's rules.

I've walked 5miles daily to a job there wasn't a bus to.

If people didn't default to buying and running their own car because of the lack of quality and provision in public transport, and its considerable expense, then all of the following would happen:

. Public transport would improve

. Public transport would become cheaper

. Work itself would change, to accommodate the limitations of public transport provision

. "I'm not well enough to walk or cycle" - for some people, walking or cycling would get them well, and might in fact be the best prescription, and the most cost-effective for the NHS.

For those who are genuinely prevented from walking or cycling by chronic illness or disability, those who can walk or cycle giving up their cars would reduce traffic congestion on the roads, making for less stressful, and slightly shorter, journey times for those who aren't able to live without a car for genuine reasons, and making the workday easier for those whose work involves driving - although, starting with a reduction in reliance on private cars could trigger a move to explore more environmentally sound methods of transporting freight, which would have their own wider benefits to society.

Equity, after all, isn't about "everyone having to do the same" - it's about those who are able to make sacrifices and compromises doing so, in order to make life easier and more equal for those who are genuinely unable to sacrifice more, or compromise further, than they already have.

For the full story of my life without the option to drive, and a discussion on the impacts, positive, negative, and otherwise, of living car-free, email theproductivepessimist@yahoo.com to book me for public speaking engagements in the UK.

For those who are genuinely prevented from walking or cycling by chronic illness or disability, those who can walk or cycle giving up their cars would reduce traffic congestion on the roads, making for less stressful, and slightly shorter, journey times for those who aren't able to live without a car for genuine reasons, and making the workday easier for those whose work involves driving - although, starting with a reduction in reliance on private cars could trigger a move to explore more environmentally sound methods of transporting freight, which would have their own wider benefits to society.

Equity, after all, isn't about "everyone having to do the same" - it's about those who are able to make sacrifices and compromises doing so, in order to make life easier and more equal for those who are genuinely unable to sacrifice more, or compromise further, than they already have.

For the full story of my life without the option to drive, and a discussion on the impacts, positive, negative, and otherwise, of living car-free, email theproductivepessimist@yahoo.com to book me for public speaking engagements in the UK.

Comments

Post a Comment